Critical Limb Threatening Ischemia: The Time has Come for a Multidisciplinary Approach

Diaz-Sandoval L

DOI10.21767/2573-4482.19.04.1

Department of Cardiovascular Research, Metro Health-University, Michigan Health Hospital, USA

- *Corresponding Author:

- Diaz-Sandoval L

Department of Cardiovascular Research

Metro Health-University

Michigan Health Hospital, USA

Email: ldiazjr71@gmail.com

Received date: November 29, 2018; Accepted date: January 22, 2019; Published date: January 29, 2019

Citation: Sandoval DL. Critical Limb Threatening Ischemia: The Time has Come for a Multidisciplinary Approach. J Vasc Endovasc Therapy. 2019, Vol.4 No.1:9.

Copyright: © 2019 Sandoval DL. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Critical Limb Threatening Ischemia (CLTI) represents the terminal stage of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Over a 5-year period, 5% to 10% of patients with either mild to moderate PAD (as manifested by symptoms of intermittent claudication) will progress to CLTI. This clinical deterioration has been associated with multiple factors, including the frantic worldwide epidemic of obesity and diabetes, as well as the aging population, and the failed attempts at controlling tobacco use; and its prevalence is expected to exponentially increase to a conservatively estimated 2.8 million patients by 2020. The contemporary management of patients with CLTI is complex due to the multifaceted nature inherent to the disease process and the multiple gaps in care that are typical of currently common practice workflows, whereby different specialists treat the patient in an isolated, uncoordinated (and therefore inefficient) fashion. Each expert takes care of “one aspect” of the patient, but everyone misses the big picture represented by the need of a simultaneous, transition less and efficient multidisciplinary approach. This article intends to illustrate what the multidisciplinary approach to the management of patients with CLTI should look like in 2019.

Keywords

Peripheral arterial disease; Critical limb threatening ischemia; Multidisciplinary team; Revascularization; Wound healing

Abbreviations

PCP: Primary Care Provider; ABI: Ankle-Brachial Index; TBI: Toe-Brachial Index; US: Ultrasound; SPP: Skin Perfusion Pressure; TCOM: TransCutaneous Oxymetry; APP: Advanced Practice Provider (Nurse Practitioner, Physician Assistant); OS: Other Specialist (Orthopedist, Diabetologist, Endocrinologist, Dermatologist); CTA: Computed Tomography Angiogram

Introduction

Critical Limb Threatening Ischemia (CLTI) represents the terminal stage of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Chronic limbthreatening ischemia has an estimated annual incidence of 220 to 3500 cases per 1 million people [1-3], and a prevalence of 1% to 2% (although it may be as high as 11% among patients with known PAD [2]. Over a 5-year period, 5% to 10% of patients with either reportedly asymptomatic PAD or intermittent claudication will have progression to CLTI [1]. This clinical evolution has been independently associated with advanced age, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and chronic renal dysfunction [1,4], and it has been determined that mechanical treatment of the disease at its early stages is not justified when performed with the intention to “prevent progression to CLTI” [5]. Atherosclerosis is the most common and most widely recognized etiology of CLTI; however it can also be secondary to thromboembolism, Buerger’s disease, trauma, dissection, vasculitis, fibromuscular dysplasia, physiological entrapment syndromes, and cystic adventitial disease [5]. The raging epidemic of obesity and diabetes, as well as the aging population, are expected to exponentially increase this number to a conservatively estimated 2.8 million patients by 2020.

The contemporary treatment of patients with CLTI is complex due to the multifaceted nature inherent to the disease process and the apparently invisible (or purposefully ignored) fragilities of currently common practice workflows, whereby different specialists treat the patient in an isolated, uncoordinated (and therefore inefficient) fashion. Each expert takes care of “one aspect” of the patient, but everyone misses the big picture represented by the need of a simultaneous, transitionless and efficient multidisciplinary approach.

It must be emphasized that the contemporary management of CLTI should include a combination of endovascular (or surgical) revascularization as the mainstay of therapy, complemented by a host of non-interventional therapies. This multidisciplinary approach should be delivered by a CLTI -team, as a continuum of care.

The “Achiles heel” of the current approach to CLTI, is the reigning “disjointment” of the pieces that should conform the CLTI team. There are multiple reasons underlying this inefficient process, which vary geographically (albeit sharing some features among regions, including prevalent conflicts of interest among specialists, secondary to archaic payment models).

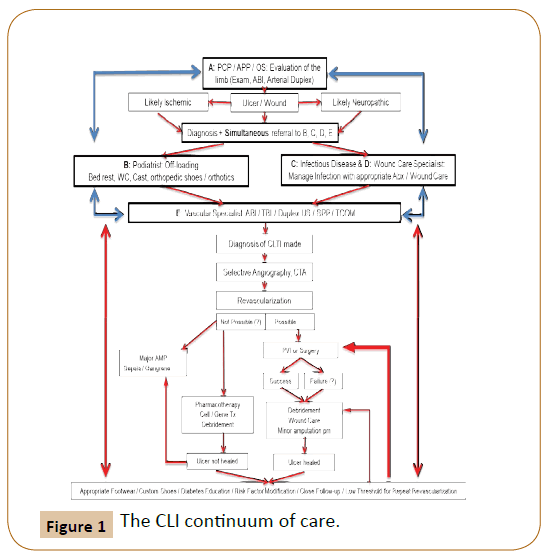

In the currently proposed multidisciplinary approach (Figure 1), the patient first enters into the continuum, at the time of the first clinical contact with any of the members of the team, who will proceed to evaluate the patient, and generate a series of simultaneous referrals to the remainder of the team. Therefore the patient can have the first clinical contact by either the Primary Care Physician (or an Advanced Practice Provider) or any of the potential members of the team (which does not require a rigid structure: this can vary between places based on available expertise), including an Endocrinologist, an Infectious Disease specialist, a Wound Care Specialist, a Podiatrist, occasionally an Orthotics Specialist as well as a “Vascular Rehabilitation Specialist”, and last but not least, the Vascular Specialist (either a Vascular Surgeon with endovascular training and experience, an Interventional Cardiologist or an Interventional Radiologist, depending on locally available expertise). The patient then undergoes a series of appropriate non-invasive vascular tests in order to:

1. Diagnose the extent of disease.

2. Plan the therapeutic revascularization strategy.

3. Serve as baseline for future surveillance studies.

The Darker cells represent the links of the chain.

If the diagnosis is made by B: simultaneous referral to A+C+D+E.

If the diagnosis is made by C: simultaneous referral to A+B+D+E.

If the diagnosis is made by D: simultaneous referral to A+B+C+E.

If the diagnosis is made by E: simultaneous referral to A+B+C+D.

Once revascularization and healing are achieved, or amputation is performed, the patient continues to be followed by members of the team who will re-initiate the referral process when faced with any signs of decline or stalled healing progress.

Vascular Specialist: Interventional Cardiologist, Interventional Radiologist or Vascular Surgeon (depending on local expertise and practice patterns).

Once the patient undergoes complete revascularization, followup by a member (s) of the team, should be continuous to ensure complete healing and post-healing surveillance. A high index of suspicion and an aggressive approach should be kept in mind, with prompt referral for repeat revascularization (of paramount importance since these patients live on a very delicate balance where perfusion is barely able to keep the metabolic needs of “healed” tissue, but will become insufficient if there is another insult to the skin barrier) in order to minimize potential complications and increase the likelihood of permanent positive outcomes. Unfortunately, currently followed protocols in clinical practice are not designed to function in this manner. Generally the patient is only referred to the vascular specialist after months of failed wound therapy or repetitive visits to the podiatrist or surgeon for serial debridements without improvement (due to lack of appropriate arterial circulation). Another weakness of this approach has been the traditional referral to specialists who are not trained in the latest revascularization techniques, leading to frequent amputations without even undergoing a basic angiographic evaluation. In the best of scenarios, patients are properly and timely referred to a vascular specialist, undergo appropriate non-invasive and invasive testing, and finally receive adequate revascularization therapy. Among these (unfortunately the minority), only a very small fraction returns for follow up with the vascular specialist, or with any of the other members of the team. Many times they do follow up with a “wound clinic” which is not affiliated with the system where the vascular specialist performed the intervention, and therefore are not familiar with the latest techniques and advances. Thanks to this disjointment, there is no communication between the members of the team that addresses the status of the patient, and many times when the patient finally comes back, the situation is worse than it was at the first encounter. Overall, there is a widespread lack of knowledge and attachment to the old ways that needs to be overcome. Unfortunately, data driven clinical studies to evaluate strategies for surveillance, use and duration of anti-platelets, anticoagulants and other risk factor modifying agents, as well as the use of non-invasive testing, and indications for repeat revascularization in these patients do not exist. Current data has been derived from retrospective studies, with inconsistent reporting standards leading to a paucity of evidence, especially following endovascular revascularization in CLTI.

Non-interventional therapies have a role as primary treatment in patients who have failed to improve symptoms (despite revascularization), and in patients who are unsuitable or unfit for revascularization. Their role is adjuvant after revascularization procedures, and when used to reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events (which are inherent to these patients and tend to be the most common cause of mortality).

Three pillars constitute the foundation of adequate contemporary CLTI treatment, and each one encompasses different goals:

1. Medical: Goals include pain control, reduction of major adverse cardiovascular events (by appropriate treatment of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, kidney disease and infections) and improvement in quality of life.

2. Interventional: Goals include revascularization to achieve limb salvage; wound care to achieve healing, and orthotics/offloading in order to achieve maintenance of ambulatory status.

3. Surveillance: Goals include close follow up and monitoring after treatment delivery and even after healing. The first sign of stalled progress, clinical decline or recurrence should prompt an immediate referral to the CLTI team.

The medical goals are tasks that should be led by the Primary Care Physician or Advanced Practice Provider in conjunction with Endocrinologists/Diabetologists. The interventional goals require the active participation of Podiatrists (or Orthopedic Surgeons, based on locally available expertise), Wound Care and Infectious Disease Specialists, Vascular Specialists, Vascular Rehabilitation and Orthotics Specialists. The surveillance goals should be a task carried by all the members of the team.

Non-interventional therapies for the management of CLTI comprise the use of preventive measures, wound care, pharmacotherapy (primary: to treat CLTI, and adjuvant: to reduce major adverse cardiovascular events and to improve post-interventional outcomes), biotherapies (cell and gene therapy), and mechanical therapies designed to achieve the goals aforementioned. The stakeholders involved are the patients, and the CLTI team members, all of whom represent a link of the chain that has to be in place in order to improve outcomes.

More recently, there has been a lot of discussion about the creation of “wound care teams” or “vascular teams”, in an effort to mimic what has occurred in the cardiac arena, where interventional cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons have finally merged their expertise and created “heart teams” which have turned into the standard of care when decisions are to be made regarding the best strategy to address a patient’s individual problem, leading to proven improved outcomes.

Prevention

Preventive measures should constitute the cornerstone of managing patients with CLTI, especially among patients without tissue loss. Primary prevention efforts should be directed at measures to avoid skin breakdowns. These include skin moisture, adequate footwear/orthotics, adequate toenail care and education on preventing foot trauma/falls. The patients need to be educated on being proactive and inspecting their feet on a daily basis, as well as to contact the team if there is evidence of any new skin breakdown, or any change in pre-existing wounds. The CLTI team should direct this effort in conjunction with the patient. In patients who have already undergone revascularization procedures, the team should expand to include physical therapy and rehabilitation specialists to help the patients get back to a functional status that improves their quality of life, previously impaired by the impediments enforced by CLTI. In those patients that unfortunately have had to undergo some form of amputation despite the best efforts at revascularization and wound healing, the addition of the Orthotics specialist is of paramount importance. Secondary prevention should address smoking cessation, blood pressure and glycemic control, lipid lowering, and antiplatelet agents. Unfortunately many patients with CLTI do not receive and /or do not follow intensive risk factor modification.

Wound Care

Meticulous wound care is critical for patients with CLTI and tissue loss. Underlying infection should be treated and necrotic tissue debrided. Topical therapies with recombinant growth factors and hyperbaric oxygen are being investigated [6]. The repetitive debridement and application of topical therapies without urgently involving the vascular specialist, is the norm in current practice in the United States and Latin America. Once again, the simultaneous participation of several members of the team represents one of the cornerstones of a successful strategy to manage the patient with CLTI and should be the direction we start to follow. All members of the team should be intimately involved with the CLTI patient from the time of diagnosis, until complete wound healing has occurred (median time from revascularization to complete wound healing is approximately 190 days) [7,8]. Female patients tend to have poorer wound healing compared to their male counterparts [9].

Hyperbaric Oxygen

There is no proven benefit of hyperbaric oxygen in CLTI as primary therapy. A Cochrane review of the effect of hyperbaric oxygen on ulcer healing in patients with diabetes concluded that the therapy increased the rate of ulcer healing at 6 weeks but not at 1 year and there was no significant difference in the risk of major amputation [10]. However these studies have been performed in patients who have not undergone revascularization. Studies directed at analyzing the adjuvant role of hyperbaric oxygen combined with aggressive wound care and revascularization would likely show faster healing times and improved outcomes.

Mechanical Therapies

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS), and intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) have been evaluated as adjuvant treatment options for CLTI patients who are deemed poor candidates for revascularization. SCS improves microcirculatory blood flow, relieves ischemic pain and reduces amputations rates in patients with CLTI. In a retrospective study of 150 patients with CLTI who failed conservative and surgical management, SCS increased blood flow and was associated with significant pain relief, improved quality of life, and increase in the transcutaneous pressure of oxygen [11]. A more recent study of 101 consecutive patients with no revascularization options found that reducing the delay between the ulcer onset and implantation of a SCS resulted in improved quality of life and walking distance [12]. Further studies should be conducted in the role of these therapies in patients who have undergone revascularization procedures and are felt to no longer have any more endovascular or surgical options, as the number of patients “deemed poor candidates for revascularization” will continue to decrease (thanks to advances in revascularization therapies).

In CLTI patients with “no revascularization options” (in quotes, as this is nowadays -in my opinion- a non-existing condition) who underwent treatment with IPC, this therapy has shown to be a cost & clinically effective solution, providing adequate limb salvage rates and relief of rest pain without revascularization [13].

Conclusion

The pathophysiology of CLTI is complex and involves both micro and macro vascular pathological features. Therefore it is not surprising that therapeutic modalities are multifold, spanning many health care specialties and requiring substantial institutional infrastructure to provide optimal patient care. Though challenging, the future of CLTI treatment is exciting with increasing focus on optimal wound care and prevention, adherence to proven medical therapies, improving revascularization outcomes with novel endovascular and surgical techniques and devices, and on-going investigation into promising therapies like therapeutic angiogenesis. Of paramount importance is the creation and establishment of the CLTI team, with aggressive referral upon identification of skin breakdowns or any other factors that can predispose the patient to a rapid decline and compromised prognosis. Patients with CLTI often have chronic wounds, and newer cell-based therapies for chronic wounds show interesting parallels to stem cell therapy for CLTI. Several human-derived wound care products and therapies, including human neonatal fibroblast-derived dermis, bi-layered bioengineered skin substitute, recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor, and autologous platelet-rich plasma may provide insight into the mechanisms through which differentiated cells could be used as therapy for chronic wounds, and, in a similar fashion by which stem cells might have a therapeutic role in the management of patients with CLTI.

References

- Farber A (2018) Critical limb threatening ischemia. N Engl J Med 379: 171-180.

- Nehler MR, Duval S, Diao L, Annex BH, Hiatt WR, et al. (2014) Epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease and critical limb ischemia in an insured national population. J Vasc Surg 60: 686-695.

- Rothwell PM, Coull AJ, Silver LE, Fairhead JF, Giles MF, et al. (2005) Population-based study of event-rate, inci- dence, case fatality, and mortality for all acute vascular events in all arterial terri- tories (Oxford Vascular Study). The Lancet 366: 1773-1783.

- Howard DP, Banerjee A, Fairhead JF, Hands L, Silver LE, et al. (2015) Population-based study of incidence, risk factors, outcome, and prognosis of ischemic peripheral arterial events: implications for prevention. Circulation 132: 1805-1815.

- Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, Barshes NR, Corriere MA, et al. (2017) AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 135: e726-e779.

- Zhang L, Chen J, Han C (2009) A multicenter clinical trial of recombinant human GM-CSF hydrogel for the treatment of deep second degree burns. Wound Repair Regen 17: 685-689.

- Soderstrom M, Aho PS, Lepantalo M, Alback A (2009) The influence of the characteristics of ischemic tissue lesions on ulcer healing time after infrainguinal bypass for critical leg ischemia. J Vasc Surg 49: 932-937.

- Soderstrom M, Arvela E, Alback A, Aho PS, Lepantalo M (2008) Healing of ischaemic tissue lesions after infrainguinal bypass surgery for critical limb ischaemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 36: 90-95.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee (1996) A randomized, blinded, trial of clopidogrel vs. aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. The Lancet 348: 1329-1339.

- Kranke P, Bennett M, Martyn-St James M, Schnabel A, Debus SE, et al. (2012) Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 18: CD004123.

- Petrakis IE, Sciacca V, Broggi G (1999) Spinal cord stimulation in critical limb ischemia of the lower extremities: our experience. J Neurosurg Sci 43: 285-293.

- Tshomba Y, Psacharopulo D, Frezza S, Marone EM, Astore D, et al. (2013) Predictors of improved quality of life and claudication in patients undergoing spinal cord stimulation for critical lower limb ischemia. Ann Vasc Surg 28: 628-632.

- Tawfick WA, Hamada N, Soylu E, Fahy A, Hynes N, et al. (2013) Sequential compression biomechanical device versus primary amputation in patients with critical limb ischemia. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 47: 532-539.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences